Nature Microbiology: On the trail of the archaeal bacteria

Archaea colonize extreme habitats, including the digestive tract of vertebrates. The various strains are specific to the host, as ICC Water & Health researchers have now demonstrated together with international partners.

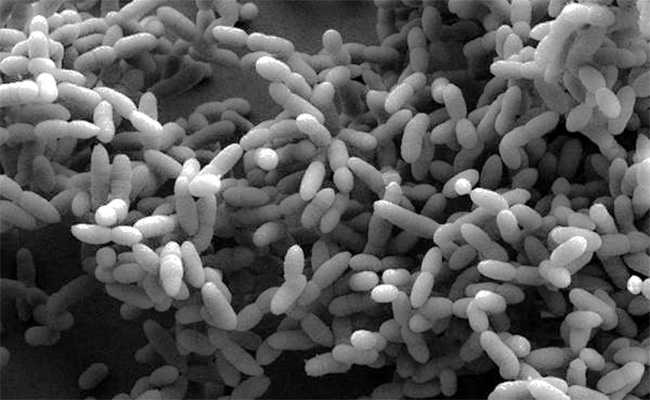

Photo: Archaeon of the species Methanobrevibacter | © Berger/MPI for Developmental Biology, Tübingen

Archaea are single-celled organisms, are at the beginning of evolutionary history and have therefore existed for billions of years. Yet it is only now, in the 21st century, that scientists are discovering new strains - those that live in the digestive tracts of humans and other vertebrates. A recent study by researchers from ICC Water & Health and the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology provides an overview of species-specific archaeal colonization. The work was published Oct. 26, 2021, in Nature Microbiology.

Drinking water research and microbiology

For years, our ICC member Georg Reischer has been working intensively on the question of how pollution in water can be measured and attributed to a polluter. Contamination sometimes comes from human sewage, but also from livestock or wildlife. "When we find fecal pollution, it is important to find the cause. We can do this, for example, by using microorganisms that specifically occur in the digestive tract of a particular species," explains Georg Reischer. This process is known as microbial source tracking. Since it is often not so easy to assign a causative agent, the scientists have set out to find new, specific markers. The cooperation between the ICC Water & Health and the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology began several years ago. A central hypothesis of our work is that there are archaea living in the digestive tract that are firmly associated with their host - and are thus suitable for causative identification.

A comprehensive data set is emerging

Studies looking at the occurrence of archaea in the digestive tract mostly use samples derived from humans or livestock, as well as primers that are non-specific for different archaea. This severely limits the amount of knowledge that can be gained. "In contrast, three-quarters of the samples we studied, which were collected with the support of Gabrielle Stalder from the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, came from wild animals of different taxa, i.e., mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish," Reischer says. "This is unique and provides us with a comprehensive picture." In the 2019 study published in Nature Communications, we already used this dataset to study the bacterial microbiome of different species.

What the research team has now discovered? Previously undiscovered archaea live in vertebrates, which have now been classified for the first time and can apparently be associated with individual animal species. The fact that archaea can be clearly assigned to an animal species or group of animals is due to two factors: Diet and degree of relatedness. "The more closely related two species are, the more similar their microbiome is - including archaea," explains Andreas Farnleitner.

Abbreviated tracking

"One particular discovery is the archaeon Methanothermobacter," says Nicholas Youngblut of the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, who decoded the gene segments of the archaea. Methanothermobacter is found in birds in high concentrations. One explanation for why this is so could be the archaea's adaptability: The single-celled organisms occur primarily in niches and are highly adapted. Some species prefer high temperatures, while others live in very acidic environments or concentrated salt solutions. "Compared to other vertebrate classes, birds have a particularly high body temperature of up to 42 degrees Celsius. This seems to be an advantage for this archaeon," says Georg Reischer. Findings like these can be used for causative identification in the future, because host-associated archaea are far more specific than conventional markers.

Link to the publication: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-021-00980-2